Akin to Japanese yakitori or Indonesian satay, the Philippines has their very own charcoal grilled delicacies. Although each region has crafted their own unique version of grilled seafood and meats — such as the lemongrass- and annatto-marinated inasal from the Ilonggo region or the headier, peanutty satti from Zamboanga — nothing is more ubiquitous than the classic skewered version fondly known as Pinoy BBQ. From street vendors to the tables of every children’s party and home celebration, barbeque is undoubtedly an iconic local favourite. This feature for BBC Travel, written by Stephanie Zubiri, explores Pinoy BBQ, the Philippines’ charcoal-grilled delicacies whose distinctively sweet, tangy flavours unite the nation.

Late afternoon sun seeped through the cracks of the mid-rise buildings, casting a golden glow on the gritty side streets of Metro Manila. Here, on the fringes of the Makati and Pasay business districts, kitschy jeepneys, whizzing motorcycles and rickety tricycles shuttled daily commuters through the snaking lanes. As always, the unmistakably sweet scent of charred barbecue perfumed the air, wafting from smoky coals being fanned on the roadsides.

Ihaw-Ihaw, which literally translates from Tagalog as “grill-grill”, is one of the most popular cooking techniques in the Philippines. “Grilling is integral to local cuisine because a lot of rural cooking makes use of wood and charcoal,” explained Chef Jordy Navarra of Toyo Eatery, named one of Asia’s Top 50 Best Restaurants in 2021. “Because of this, I think the whole idea of ihaw is at the centre of a lot of Filipino food. It’s a way of cooking that is simple, and can be done wherever you are, especially if you have no access to gas or electricity.”

The regional incarnations of grilled seafood and meats are manifold, from the lemongrass- and annatto-marinated inasal from the Ilonggo region to the headier, peanutty satti from Zamboanga province. However, nothing is more ubiquitous than the classic, skewered version fondly known as Pinoy BBQ (Pinoy is the shortened, colloquial word for Filipino).

Whether bought from a street vendor, eaten at a child’s birthday party or ordered at one of the country’s top tables, this barbecue is an iconic favourite across the nation. “Pinoy BBQ is one of those dishes that stands out when recounting my memories of food growing up,” Navarra said. “Celebratory cooking in my family’s household always included some form of grilled food. My lola (grandmother) used to run a palengke (wet market), and outside it were barbecue joints that we would always buy from. To this day, it’s still one of our go-to foods, whatever the occasion may be.”

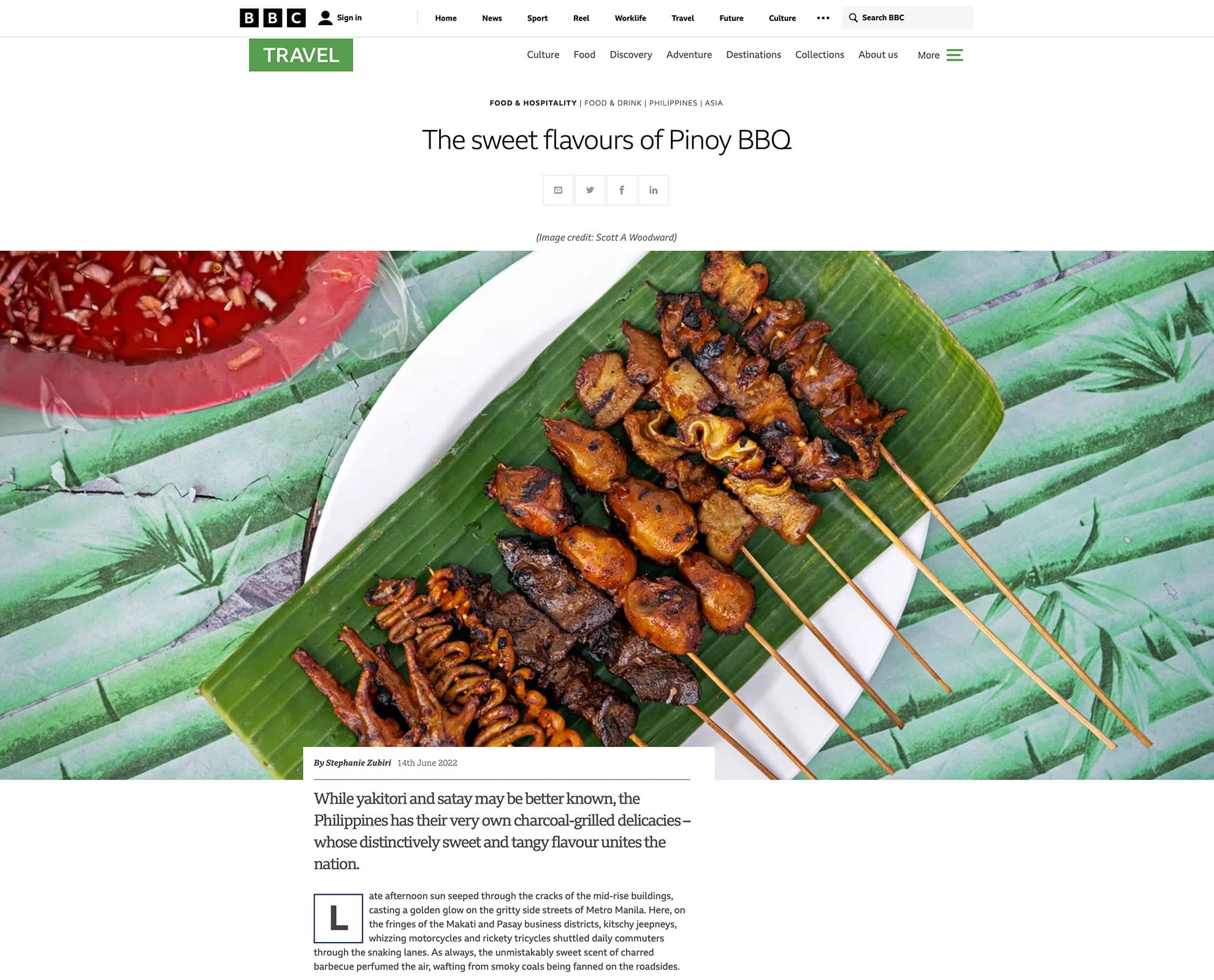

Though it’s broadly popular, it comes in many varieties: approachable pork or chicken skewers; the more adventurous isaw (intestines); Betamax (rectangles of coagulated pig’s blood that resemble the 1980s AV tapes); and Adidas (chicken feet, colloquially named after the famed sneaker brand). But all Pinoy BBQ has one thing in common: the marinade. Made with soy sauce, calamansi (an indigenous, fragrant citrus fruit), banana ketchup and lemon-lime soda, and served with a dipping sauce of spicy vinegar, the result is a chargrilled treat with the distinctive sweet and tangy flavour Filipinos love.

While there is no record of the precise origins of this unique marinade, it is widely acknowledged that the trend of preparing barbecue in this manner began in 1950s Metro Manila before expanding to other urban centres.

This was at the height of American cultural influence, a phenomenon that has its roots in the American colonial period in the Philippines (1898–1946), which then flourished due to a continued strong military presence in the country. Some hypothesise that the sauce is meant to emulate the smoky, zesty and rich flavours of the barbecue glazes from the American South.

Pinoy BBQ’s distinctive sweetness and caramelisation comes from two integral, albeit unusual, ingredients: ketchup and soda. These were introduced during the American Commonwealth Era in the mid 1930s and popularised post-World War Two. “Somehow, locals perceived that imported elements such as soda and ketchup would lend ‘deliciousness’ to a dish because they are ‘imported’ and ‘from America’,” explained Ige Ramos, food historian and author of Dila at Bandila: Search for the National Palate of the Philippines.

However, the scarcity of tomatoes during WW2 led to the invention, mass production and popularisation of banana ketchup, a local and less-expensive alternative to the American condiment that’s made from bananas, vinegar and spices. Its sweeter profile appeals to many, making it a mainstay on the tables of all Filipino homes and giving a distinctly candied quality to the BBQ glaze.

And what of the lemon-lime soda? “I would have thought the primary purpose of using 7UP was to mask the strong smell of meat that had been exposed to the elements,” Ramos said, “but street food vendors swear by the efficacy of carbonated water to tenderise cheap cuts of meat.” He explained that in the marinating process, the sugar and citrus flavours create a crunchy, caramelised film on the meat, especially around the fat, after it has been grilled.

“One can also presume that it’s this very marinade that defined the urban Filipino taste buds with a preference for sweet-tasting food,” Ramos said.

BBQ vendors ply their trade from street side stalls at transportation hubs and simple tables and grills placed outside homes, churches and school yards — as well as at more established restaurant chains and via delivery services. Aside from its comforting taste, the appeal of barbecue lies in its value for money, with a skewer ranging from just 12 to 50 pesos (£0.18 to £0.75). According to Micky Fenix-Macabenta, president of the Food Writers Association of the Philippines, the well-loved snack is not merely something to eat, but a way of life. “Barbecue has a culture of its own,” she said. “It’s a place where people gather, interact and share stories. Often you’ll find these stalls grouped together in a plaza or on a street corner, and late in the afternoon it’s a very vibrant scene.”

Ramos agrees. “There is an emotional and almost spiritual quality to barbecue,” he said. “It can be shared with friends for a birthday party along with lumpiang shanghai (spring rolls) and pansit (noodles); it serves as pulutan (bar snacks) for happy hour and when dining alone, it still conjures happy memories.”

While there are myriad places to try Pinoy BBQ, and everyone has their favourite spot, Ramos recommends Aling Sosing’s in Pasay. When we visited, the carinderia was packed full of ravenous diners with a long queue that wound up the street. A slim, energetic man was at the grill, darting quickly amidst the bellows of thick smoke, clicking his tongs rhythmically while flipping and dispatching charred whole tilapia, glistening pork belly strips and skewers of barbecued pork.

Established in the 1970s, the business is still family-owned, with Aling Sosing’s daughter-in-law, Gemma, and granddaughter, Mimay, running the show. “My grandmother started small, serving breakfast and a few dishes like nilagang baka (boiled beef soup) for jeepney and taxi drivers,” said Mimay. “Slowly, she kept adding more dishes, and people from the offices in Makati would cross over to eat here.”

The mood was festive, and every table had some kind of grilled specialty, shared family-style alongside mountains of rice, bowls of broth and myriad condiments such as fresh bird’s eye chilli, soy sauce and vinegar. Their skewers and liempo (pork belly) had a salty profile, with more umami than many places, making it a perfect ulam (main dish) rather than a simple snack.

Despite serving up a more savoury, high-end version of BBQ at Toyo (using three cuts of pork and an ultra-concentrated reduction glaze to highlight the meaty flavours), Navarra remains a big fan of the classic street version. “I like to discover places recommended by my colleagues, and our master bread baker, Sherwin, introduced me to Aling Bebeng’s BBQ,” he explained. Located on the corner of Makati’s Washington and Roosevelt Streets, the small charcoal grill, flanked by a table and a few stools, is one of the most popular barbecuhans (street grills) in Metro Manila due to the extra-sweet marinade and tender, plump cuts of meat. “It’s become a favourite haunt for merienda (a late afternoon snack) for the whole Toyo team,” Navarra said.

“It crosses the social divide,” Fenix-Macabenta said. “If you are Filipino, you will like it because of its sweet and nostalgic flavours.”

And although it can be enjoyed anytime, anywhere, the consensus is that barbecue is best fresh off the coals, on the street. “Everyone has a shared experience when going to a barbecue stall, from picking out which skewers you want to eat, to watching and waiting as the meat is cooked, then dunking them into vinegar,” said Navarra. “It’s an experience that so many people can relate to, wherever in the country you are.”

There’s a social etiquette with unspoken rules about enjoying your Pinoy BBQ street-side. Large vats of spiced vinegar sit alongside the grill where diners can dunk their fare. Double dipping is not allowed for the tightly skewered pork BBQ, but larger chunks such as Betamax can be moved apart and re-submerged, as long as it has never touched your lips.

Whether an office worker, jeepney driver or student, people from all walks of life stand side-by-side at these stalls on a daily basis to enjoy these practical and delicious treats. Pinoy BBQ is the great equaliser.