As a relative newcomer to the Philippines, photographing this feature for CNBC Traveler — alongside food and lifestyle journalist and best-selling cookbook author, Stephanie Zubiri — was a wonderful introduction to Filipino food and the history, evolution and current state of the cuisine, both locally and abroad. Browse our story published online this week.

With some 12 million people across more than 100 countries, the Filipino diaspora is one of the largest in the world.

Yet the food of the Philippines isn’t as widely known as some Asian cuisines. Fans of the cuisine argue that adobo — chicken or pork braised in soy sauce, vinegar, garlic and peppercorn — should be as recognizable as phad thai, ramen and shrimp dumplings.

As more Filipino chefs gain international recognition, the popularity of Philippines cuisine is gaining traction. In 2015, Antonio’s Restaurant — helmed by Filipino Tonyboy Escalante — was the first restaurant in the Philippines to break onto the World’s 50 Best list, debuting at No. 48.

In 2016, Bad Saint, the Washington, D.C., restaurant launched by the James Beard award-winning chef Tom Cunanan, was named the second-best restaurant in America by Bon Appetit magazine. That same year, Manila’s Margarita Fores was honored as Asia’s Best Female Chef by the U.K.-based 50 Best organization.

Yet insiders say struggles to popularize Filipino food come from stereotypes abroad as well as issues within the Philippines.

FROM MANILA TO MIAMI AND PARIS

Cheryl Tiu, a Manila-born food journalist and founder of the Miami-based events website Cross Cultures, attributes some of the problem to “hiya,” meaning shame in Tagalog, the national language of the Philippines.

“We were colonized for so many years, and we were made to think that anything imported was better,” said Tiu. “Thankfully, today’s generation has been loud and proud about our heritage.”

Television hasn’t been helpful either, said Tiu.

“We’ve also received so much bad press in the sense that some of our dishes were ‘Fear Factor-ized,‘” she said. “Many associate all our food with that.”’

Some of those sentiments were echoed by Paris-based Filipina chef Erica Paredes.

“It almost seems as though we never thought that our food was good enough to put on the global stage,” she said.

Executive sous chef Carlos Villaflor harvests fresh greens from Gallery by Chele’s terrace.

L: Chef JP Anglo in Sarsa Kitchen+Bar. R: Chef Jordy Navarra in Panaderya Toyo bakery.

Seared scallops with fennel and sinigang (a clear sour soup traditionally made with tamarind) and Korean-style fried chicken with adobo sauce are just some of the dishes Paredes is making at the Parisian cafe Mokoloco, a stint which has garnered praise from Vanity Fair and other press.

“Nowadays there’s more pride and fire in a lot of young chefs to be authentic, and that includes incorporating flavors that bring us joy and comfort,” she said. “It’s as if we were waiting for permission, but now – no more.”

WHAT EXACTLY IS ‘FILIPINO FOOD’?

“We love our sour stuff,” said television personality and chef JP Anglo of Manila’s Sarsa Kitchen+Bar, when asked to define Filipino food.

Like many cuisines, the food of the Philippines evolved for taste and necessity. Cooking with souring agents helps preserve food in the warm tropical climate. It’s the same reason foods that are fermented, dried and pickled are common too.

“We get our souring flavors from fruit such as tamarind, batwan and calamansi … we also have different sorts of vinegars,” said Anglo. “We also have our dried fish and our fermented shrimp like bagoong or ginamos, which lend strong and pungent flavors.”

Basque chef Chele Gonzalez of Gallery by Chele made the Philippines his home in 2010. Welcomed and celebrated by the local community, he offered a frank assessment of the flavor profile.

“The majority of Filipino food has a very particular taste between sweet, sour and salty — sometimes, for us foreigners, it is very difficult to understand,” he said. “With chefs like JP Anglo and Jordy Navarra, it’s becoming more sophisticated and nuanced.”

MANY ISLANDS, MANY INFLUENCES

Chef Jordy Navarra of Manila’s Toyo Eatery, No. 49 on Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants list this year, said Filipino food is difficult to define because it varies across the country — a nation of some 7,107 islands, 22 regions and eight major dialects.

Gallery by Chele’s take on a Filipino street food called taho, a sweet treat made with goat milk custard and fresh strawberries from Luzon island.

On Gallery by Chele’s tasting menu, blue crab is topped with fermented tomato sorbet, a smoked fish dashi and garnished with crystallized tibig (a type of local fig).

language and, in modern times, a fondness for fast food, sweets and processed products.

“Filipino cuisine can include a peach mango pie from homegrown fast-food chain Jollibee, even if we don’t have peaches,” said Navarra. “It can also mean sinigang using sampalok (tamarind) from the tree in your yard and pork grown by your neighbor.”

Chef Anglo said elevation of his country’s food needs to start at the local level.

“I look at our Asian counterparts like Thailand, where the street food is incredible,” he said. “I want to see this movement at a grassroots level here too.”

He said he wants to highlight street vendors — “the little guys in the provinces” — who are cooking “amazing traditional dishes” so that they can succeed too. Then, he said, “everyone around them can follow suit.”

“One of the most beautiful aspects of Filipino food is its diversity,” he said. “There are a variety of regions and islands that represent the food we eat all around the country … the more we learn and understand, the more we can express and share what we eat to the world and to each other.”

History plays a role too.

At the heart of Sino-Indo-Malay pre-colonial trade routes, the Philippines was a melting pot of cultures before the Spanish arrived in 1521. During more than 300 years of Spanish rule — a period which included Mexican influences due to the Galleon trade route that ran between Acapulco and Manila — the cuisine became heavily infused with Latin influences and ingredients.

In 1898, Spain ceded control of the Philippines to the United States following Spain’s defeat in the Spanish-American War. Thus began a period of American cultural influence in the Philippines which included the English

Chef Jordy Navarra (center, with his team at Toyo Eatery) said staying open and surviving the pandemic is a feat onto itself.

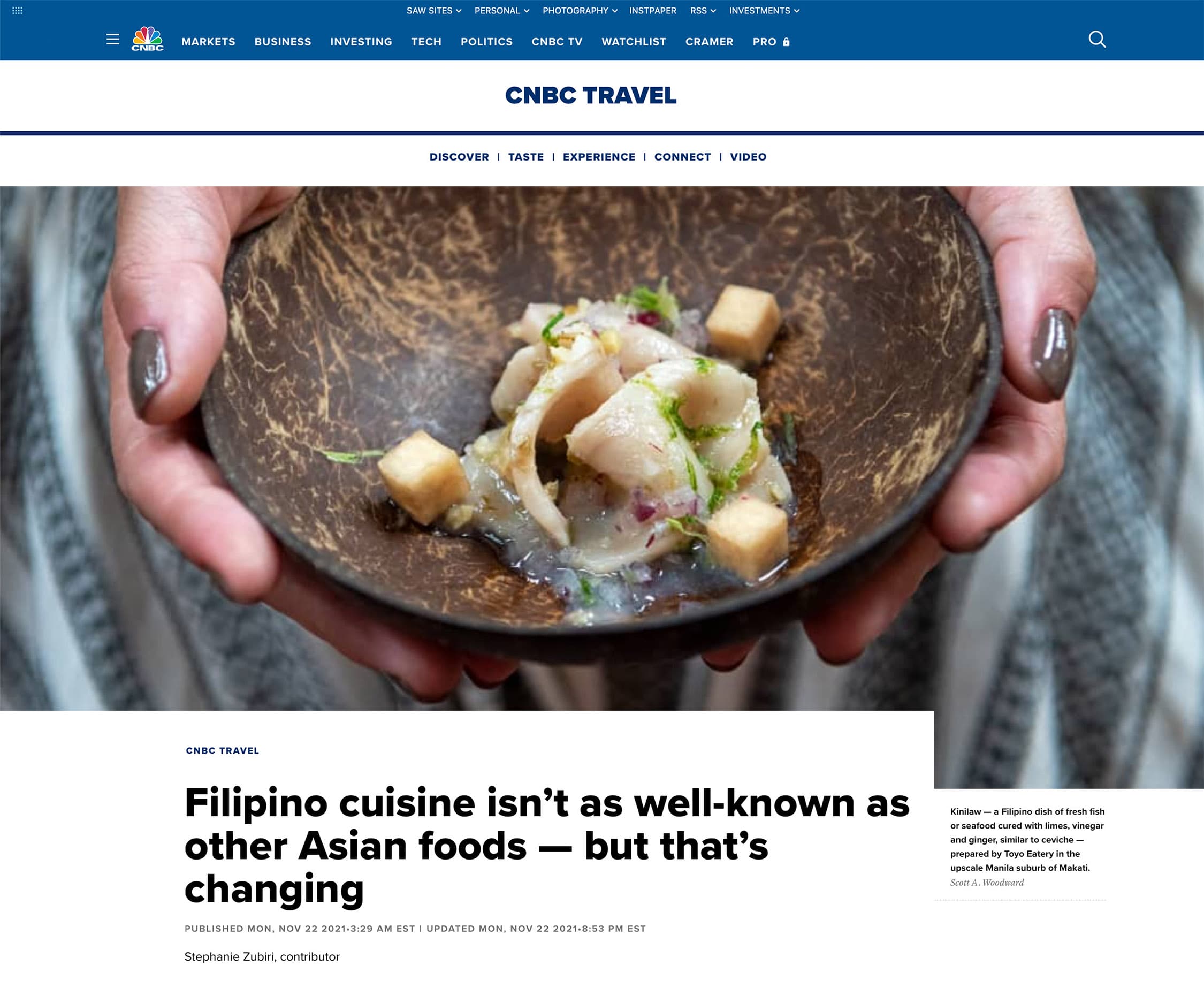

Kinilaw — a Filipino dish of fresh fish or seafood cured with limes, vinegar and ginger, similar to ceviche — prepared by Toyo Eatery in the upscale Manila suburb of Makati.

‘AUTHENTICITY’ IN AN EVOLVING CUISINE

One of the biggest setbacks for Filipino cuisine is so-called “crab mentality” — a widely used term in the Philippines to describe the act of pulling down a successful person near you. (The term is derived from crabs in bucket, which tend to pull down a crab that’s close to escaping.).

In the Philippines’ culinary world, that often comes in accusations of being “inauthentic.”

“For me, being authentic and being traditional are two very different things,” said Paredes. “I cook based on my experiences, and as someone who grew up in Manila, lived abroad and now resides in France, using seasonal European produce paired with Filipino or Southeast Asian flavors and spices is very authentic to me.”

Navarra said he travels to learn about what Filipino food means to the people around the nation. To him, being authentic is about “making sure we represent the people and communities that inspire us and our work.”

The consensus among the chefs interviewed for this report is that if the flavors are inherently Filipino — if it has that comforting savory, sour, garlicky taste — then the food is legit.

WHAT’S NEXT

“We are in the middle of a revolution, and it’s very exciting,” said Gonzalez. “Nuanced flavors, playing with textures, mixing traditional and modernist techniques — all of these things are elevating the culinary scene.”

Perhaps the biggest vector in the rise of Philippine cuisine is a crop of chefs that is staunchly unapologetic.

“We are owning it,” Anglo declares. “Chefs like Tom Cunanan or Anton Dayrit in the U.S. are not saying it’s their take on Filipino food or that it’s Fil-Am cuisine … this should be the movement.”

“We need to be bold,” he said. “This is who we are, this is our food and we love it.”

See more of my Philippines editorial work and read more of my CNBC Travel features in collaboration with writer Stephanie Zubiri.

A baker in Panderya Toyo dusting bicho — a local version of beignets — with sugar and cacao.

Panaderya Toyo creates classic Filipino breads and pastries with modern touches. The recipes follow the local tradition of using sweet and chewy dough.