Welcome to the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve,

an unlikely wild corner of modern-day Singapore.

Tucked away in the northwest of the island, this

mix of mudflats, mangroves, tidal ponds and

coastal forests feels wonderfully distant from

the clean streets, luxury malls and gleaming

skylines the city state is known for.

From Thailand to Australia, from Laos to India and from the Philippines to Japan, my friend — and the former Managing Editor of Singapore Airlines’ SilverKris inflight magazine — Nick Measures and I have been collaborating on travel stories for a number of years. Since we’ve both been grounded in Singapore since March, however our ability to partner on international features has become impossible. So Nick and I started looking more closely around our own backyard for inspiration: colourful locales, engaging characters and intriguing stories right here in Singapore. We’ve found quite a few ideas, and this one — about the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, an unlikely wild corner of our modern-day city-state — was commissioned by the South China Morning Post.

The air is heavy and still, the only movement the aerobatics of a lone bat finishing its night’s hunt. Across the strait, the lights of the condominiums in Johor Bahru, Malaysia, glitter, while the silhouette of the Eagle Point hide looms out of the predawn light, seeming to hover over the water.

The silence is shattered by the jarring squawks of a white-bellied sea eagle, an early bird heading out to catch fish for breakfast. The noise seems to act as an alarm call: an unseen woodpecker unleashes a series of rat-a-tat-tats; a striated heron sporting a black cap and grey wings peers into the water; a stork-billed kingfisher flashes past in a blur of red, orange and blue.

Welcome to sunrise at the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve (SBWR), an unlikely wild corner of modern-day Singapore. Tucked away in the northwest of the island, this mix of mudflats, mangroves, tidal ponds and coastal forests feels wonderfully distant from the clean streets, luxury malls and gleaming skylines the city state is known for.

Stepping off the coastal boardwalk, we find ourselves surrounded by the overhanging sea hibiscus that crowds the path, which divides the mangrove swamps from the sea. Rustles, pops and croaks reach us from the undergrowth — a tangle of roots and pyramids of mud (the work of mangrove lobsters) — hinting at the rich biodiversity concealed within.

“I always bring visitors here, to show them that you don’t have to go overseas, to places like Taman Negara [in Malaysia],” says retiree James Ho, who stops to chat as we admire a spider’s web hanging across the coastal trail. “It’s just as beautiful and rich in wildlife here.”

Although SBWR covers only 130 hectares, or 320 acres (less than a tenth of the size of Hong Kong’s Mai Po Marshes, in the New Territories), its diversity of habitats means it’s home to an impressive array of wildlife. Smooth-coated otters, monitor lizards, reticulated pythons, mangrove lobsters, archer fish, mudskippers, horseshoe crabs and the largest concentration of king cobras in Singapore are just some of the species found here — not forgetting the reserve’s estuarine crocodiles.

“People often don’t believe us about the crocodiles, they don’t think the signs are for real,” says SBWR director Yang Shufen, pointing to one of the warnings that dot the reserve, advising visitors to keep clear of the water’s edge.

Any lingering doubts on that front are dispelled as we emerge onto a bridge crossing a small inlet. There below us is a crocodile three metres (10 feet) long, jaws wide open to reveal very real teeth.

“See, see I told you that they are really here,” squeals a lady as she grabs her friend’s arm in mock alarm.

But it’s not the crocodiles that make SBWR such an important site for conservation. Up to 280 species of native birds have been recorded within the reserve’s boundaries and, every year between October and March, they are joined by thousands of visitors that rest on the reserve’s mudflats during an epic annual migration.

Part of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, which includes a series of wetlands stretching from the steppes of Russia to Australia’s west coast, SBWR is “Singapore’s global contribution to the conservation of biodiversity”, says Dr Ho Hua Chew, vice-president of Singapore’s Nature Society.

The retired philosophy professor, 74, was a member of the Nature Society’s Bird Group when it first identified Sungei’s ecological importance, in the late 1980s. In a landmark case for conservation in Singapore, the society successfully petitioned the government to prevent the land being used for intensive commercial farming.

In 1989, around 87 hectares were set aside to become a nature park. Having opened to the public in 1993, it became a nature reserve in 2002, its boundaries having been expanded to the area SBWR occupies today.

“It was the first time we really asked the conservation question: what do we want as a nation?” recalls Yang, who has been with National Parks since 2006 and cites a visit to SBWR as a student as the catalyst for her career.

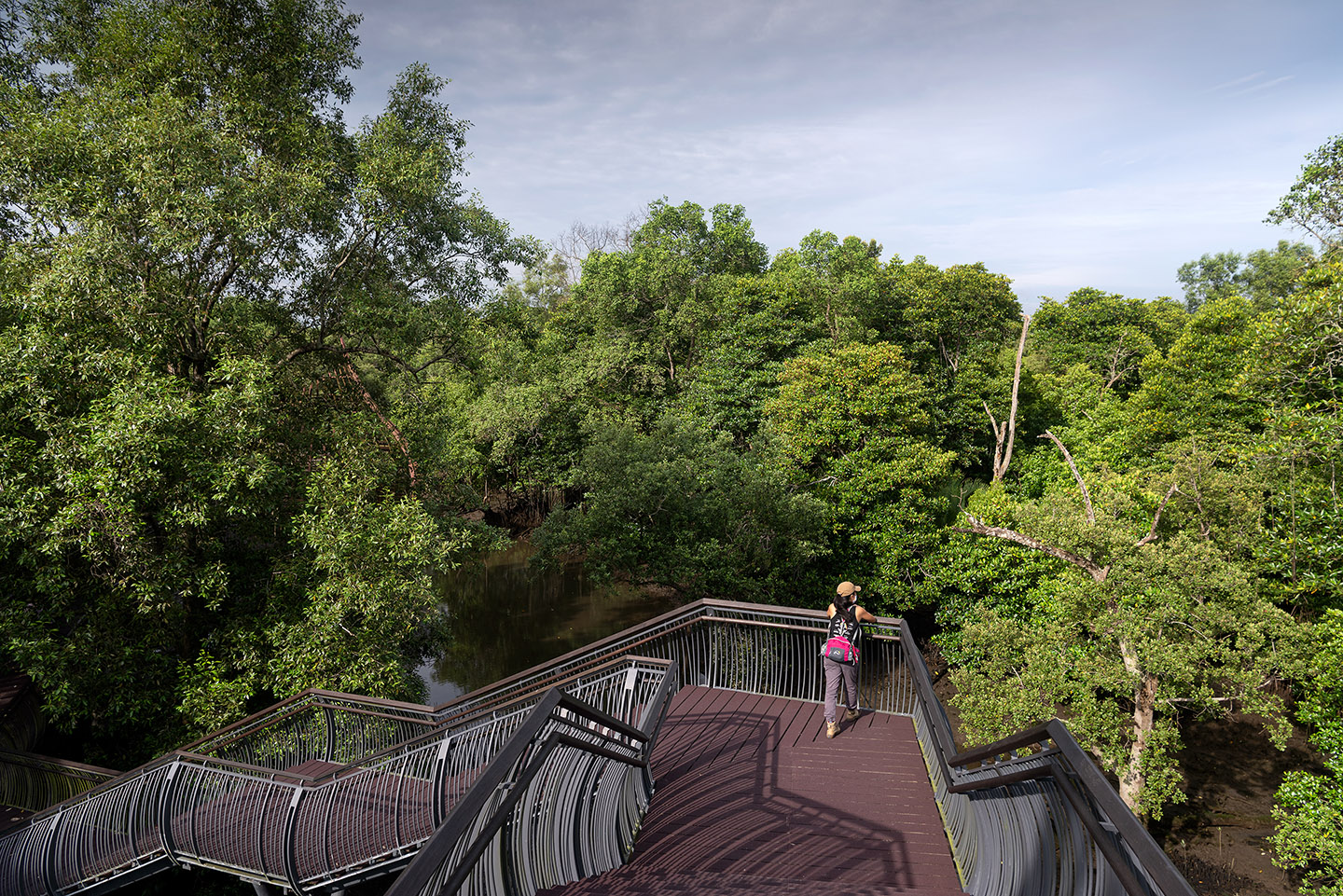

Standing at the top of the central observation tower, with its commanding views over the reserve, it is easy to understand her sense of wonder. With low tide approaching, flocks of whimbrels, redshanks and golden plovers bank sharply over the trees before landing at one of the tidal ponds that make up the core of the reserve.

These pits of scrubby grass, thick mud and shallow pools are rich in worms, crabs and molluscs. The air is filled with the sounds of the shorebirds, as they busy themselves with the task of feeding.

Wooden hides dotted around the ponds offer a ringside seat at this annual event, while the rough gravel track that makes up the 2km (1.2 mile) migration trail, hemmed in by trees, promises encounters with oriental pied hornbills, otters, tailor birds, paradise tree snakes and the occasional monitor lizard sprawled across the path.

Soon there will be even more for visitors to enjoy, and more protection for the wetlands, thanks to the creation of the Sungei Buloh Nature Park Network, expected to be completed in 2022. The existing wetland reserve will be bordered by two new areas: the Mandai Mangrove and Mudflat Nature Park, to the east, and the Lim Chu Kang Nature Park, to the west, with park connectors linking up the existing Kranji Marshes, to the south. The completed network will cover an area of more than 400 hectares.

The plans include new grassland habitats, an extra 5km of trails and an exhibition space. Part of Singapore’s drive to become a City in Nature, the plans show how far attitudes to conservation and the environment have changed in the past 40 years.

Our morning stroll ends at the wooden bridge spanning the Buloh Besar estuary that connects the tidal ponds to the Wetlands Centre, and the other half of the park. It’s expected to be replaced with a new bridge downstream, but for now remains Yang’s favourite spot.

As the clouds skim across the sky and the slow-moving water slips below our feet, the scene is buzzing with life. On one bank, a pair of rare juvenile black-crowned night herons peek out from the undergrowth, a perching blue-throated bee-eater offers a burst of vivid colour against the leaves, and white egrets pick their way through the shadows. Fish glitter as they leap from the water and a monitor lizard glides upstream.

Says Yang, wide-eyed delight in her eyes, says: “It’s just like a BBC nature documentary.”

See more of our work for the South China Morning Post, including our feature about Singapore’s emergence as the space technology hub of Southeast Asia, here.

Share your thoughts