Committing their lives to preserving art, culture and religion,

and promoting local produce and cuisine, these individuals have discovered

and harnessed their ikigai — their “reason for being.”

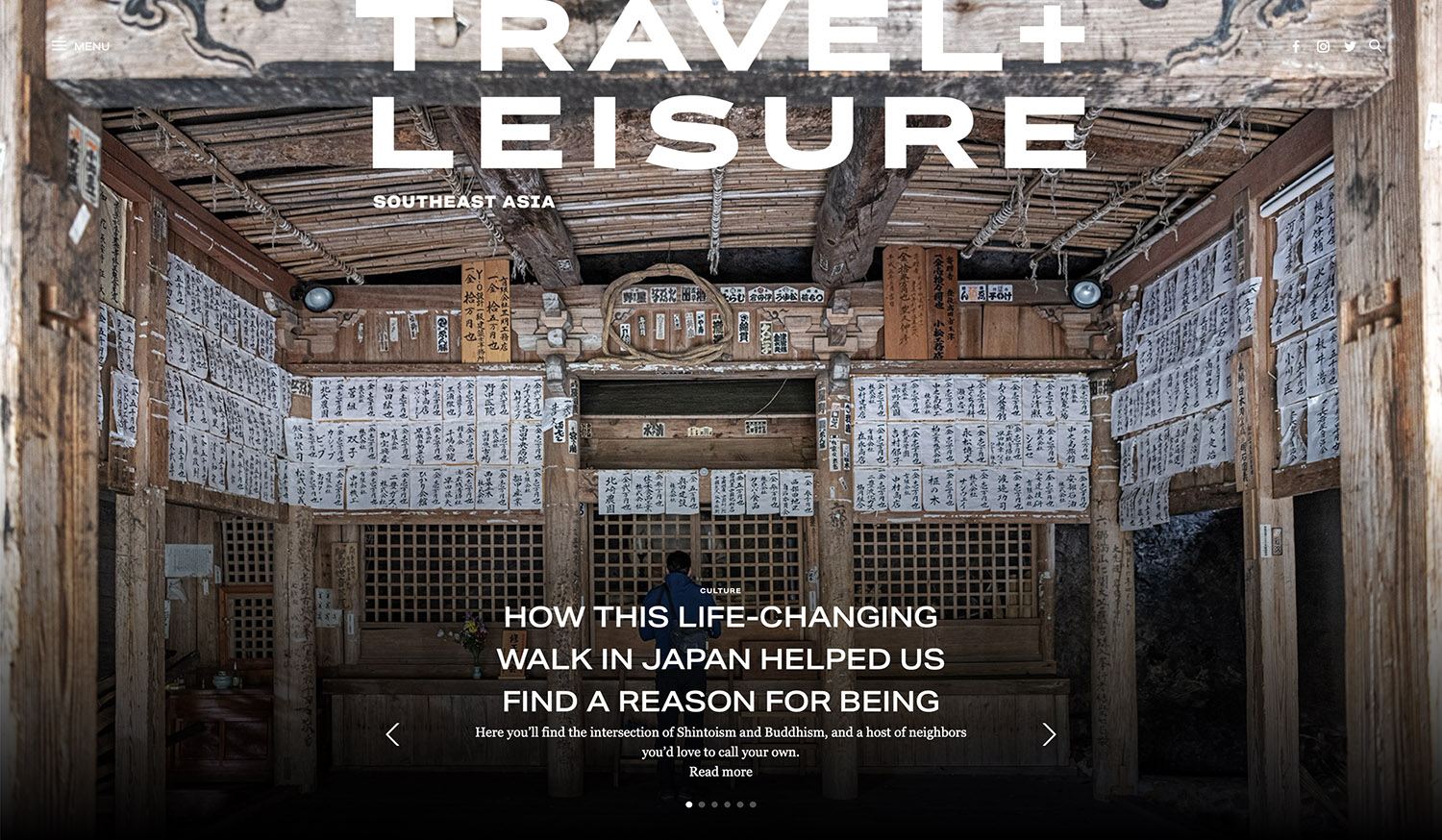

In late 2019, writer Stephanie Zubiri and I were commissioned by Silverkris, Singapore Airlines’ inflight magazine, to embark on a five-day walk across the Kunisaki Peninsula in Japan. Together we were in search of the spiritual intersection of Shintoism and Buddhism and looking to meet the endearing residents whose legacies are woven into the landscape. This month, our friends at Travel + Leisure Southeast Asia published online a broader selection of my photography — along with Stephanie’s first-person account — of the adventure.

I arrived in the onsen town of Yamaga one day ahead of my Walk Japan tour group and found myself with some extra time to explore the mysterious Kunisaki Peninsula on my own. I grabbed a map — indecipherable to me, in Japanese — and wandered off on foot to explore the sacred site of Kumano Magaibutsu, just a few kilometers away.

Hidden within a thick cedar forest, at the pinnacle of precipitous stone steps, believed to have been laid overnight by a mystical creature called Oni, sit two impressive stone relief carvings depicting Buddhist deities that date back to the late Heian period between the 9th and 10th centuries.

Next to these is a small wooden shrine, one of the thousands dedicated to Hachiman — the ancient Shinto god of war, divination and culture — that to this day remain under the helm of the prestigious Usa shrine. This unique synchronism of Shintoism and Buddhism, a cornerstone of Japanese religion and culture, is both consequential and palpable on the peninsula; it is here that shinbutsu shugo, the practice of combined worship, began more than 1,300 years ago.

I took pause on a bench in front of the temple, beside a tree with a thick rope tied around its circumference. I sat for a while in silent reflection, staring at the blue skies through lacelike golden Japanese maple leaves, and felt peaceful, almost spiritual. The following day l learned from our guide that in Japan, trees with ropes are considered spirit trees. It seems I knew intrinsically that there was something unique about this place.

Most of the Japan I have experienced over the years is the frenzied, feverish, vibrant and visceral kind found in the giant Lost-In-Translation-esque metropolises of Tokyo and Osaka. Even Kyoto, with all its quaint and historic glory, still beats with a perceptible energy. It was only when I spent five days trekking across the northeastern tip of Kyushu that I felt I finally managed to glimpse this nation’s beautiful soul.

While moving through Kunisaki’s sacred forests and scenic countryside, stopping to rest in cozy ryokans and indulging in deliciously fresh local cuisine, I encountered incredibly passionate people who thrive in this unique environment and its tangible spirituality. Committing their lives to preserving art, culture and religion, and promoting local produce and cuisine, these individuals have discovered and harnessed their ikigai — their “reason for being.”

Fuki-ji Temple

Nestled in the quaint town of Bungo-Takada is the 900-year-old wooden Buddhist temple, Fuki-ji. This historic temple was once the private sanctuary of the head Shinto priest of the nearby Usa shrine and has become a symbol of the unique spiritual symbiosis of Buddhism and Shintoism that characterizes the Kunisaki peninsula. Fuki-ji has been under the care of the Kono family for three generations.

“I believe it is important to keep the temple culture alive for the future generations,” Junyu Kono, Fuki-ji’s 39-year-old vice monk, told me. “Even if the Japanese aren’t all that religious anymore, at each turning point in their lives they seek salvation in temples or shrines. A temple provides spiritual

shelter, a place where people can come, speak to their higher selves and a higher being, and to find peace within.”

“My son does not need to follow my footsteps into monkhood. As long as he is in a position to help other people, he will find his inner peace and happiness,” Junyu said. He and his family also run Fukinotou ryokan, which sits beside the temple and is famous for his handmade soba.

Junyu discovered his passion for food during his training as a monk. “I learned to really appreciate food and contemplate its meaning,” he explained. “I find that there is a parallel in what I do and making soba. Every day I try to find that balance between being a monk and taking care of people at the inn and my family. When I make the noodles, I tried to find that same balance.”

Choan-ji Temple

At the end of a two-hour hike through lush cypress forests, Choan-ji temple waits on the mountainside overlooking the Kunisaki peninsula. “I’ve been a monk’s wife for as long as I can remember,” laughed Setsuko Matsumoto, the 84-year-old temple caretaker. “When my husband died, things became extremely difficult.” Her son is now the abbot on weekends and special occasions but is a practicing dentist.

“A few years ago, we had to replace the roof — we barely had any funds for repair.” Although seemingly physically isolated, Setsuko never feels alone. “The community came to help, and the stock market paid for the rest!” she exclaimed with a big smile. “Since the internet has arrived, I dabble every day in the stock market and do quite well for myself!”

Ota

When we first stepped into Mameno-Monya Café, we felt the spirit of the former inhabitant — an old lady who loved to nourish and nurture her family and friends,” Shinobe Murakami explained about the isolated old house she and her husband, Junya, purchased and transformed into a dining space. “We immediately thought that this should be the driving principle behind our café: to bring people together.” Shinobe met Junya, a guitarist, in Tokyo and they decided to move away from the frenetic city life in order to connect with nature and help the aging rural communities.

“Our love for the people of our community keep us going,” Shinobe told us. “Because the whole community is aging, just being the only young people here is a very big help. We assist in clearing the fields, participating in festivals and offering extra manpower. In turn, they visit our café and support our business.”

Kunimi

“The nature of Kunisaki is my inspiration,” declared Konomi Wada, a specialist in the restoration of ancient scrolls and byobu screens. “I often ponder the unique history of the peninsula, where Shintoism and Buddhism co-exist; it’s a true sanctuary.” Konomi has always lived in this house, a former brewery named Tourinryo built by her grandfather.

This once-sleepy town is now an artists’ enclave with a biannual festival that she co-founded 10 years ago. “I have always had kabuki friends who would perform in the temples and shrines here. Now there are more artists from different disciplines settling here. I love how people here are so connected with the esoteric and it transcends into my work.”

When we arrived at the train station, we were welcomed by a very handsome young man. “Hi, I’m Yo,” he said with an unexpected American twang. Yo Murakami, our guide for the day, was born in Okinawa and raised near the U.S. military bases there. “I grew up with such an American influence, I was even running a hip-hop clothing store. I always liked being different, but then I wanted to get to know my Japanese history and culture more — to connect to my roots through travel and by sharing it with others.”

Kitsuki

We wandered into the 280-year-old Tomaya Tea Shop while waiting for our car to pick us up. We sat, browsed and sampled tea. The house was run by a beautiful elderly woman, Takako Inoue. Everything about her exuded a timeless elegance. She refused to disclose her age, laughing daintily at the question.

“I was just 20 when I married into this family,” she shared. “And completely clueless about tea. My husband’s family has owned this teahouse for 10 generations.” It took her five years to learn how to perform a proper tea ceremony. “I love the slowness of it all. How symbolic each movement is, how graceful it all has to be. Today, it seems everything moves so fast and that the good old Japanese culture is fading away. It’s important to keep these traditions alive, that’s why I love working in this teahouse.”

Seventy-three-year-old Nakano Seizuo is quite the character. Eccentric and full of energy, he runs Nakano Shuzo Sake brewery that has been in his family for five generations. He welcomed us into his tasting room with the usual marketing dog-and-pony show. However, when he walked us into his brewery, his entire demeanor changed: his eyes lit up joyously and he excitedly shared his secret to making excellent sake.

“I play Mozart in my brewery! A little Chopin, but definitely no Beethoven or Beatles.” According to him, the yeasts and molds necessary for fermentation need a pleasant and calm environment to thrive. “There is no perfect formula, and ultimately no perfect sake. Everything comes from the heart and that’s what makes good sake.”

Tetsuo Nakahara

Our guide for this epic trip, Tetsuo Nakahara, or Tetsu for short, had a very distinct surfer vibe. Athletic and fit, he exuded that signature nonchalance and relaxed energy that reminded me more of coastal islands like Siargao or Bali than rural Japan. “I’m a native of Oita,” he shared proudly of his local heritage. “But I grew up in the 80s and was obsessed with MTV. I wanted to see the world and experience a different culture, so at 18 I left for Florida… Eventually I ended up in California and became a professional beach bum.” From Baja, Mexico, to Hawaii, Tetsu worked as a dive instructor and then journalist, eventually settling in Tokyo where he met the love of his life.

“We both decided to move back here to Oita. In my village, there are only 13 houses with 13 families — most of them are in their seventies. They are so excited that we are having a baby because it has been more than 12 years since they’ve had a baby in this village!” When asked what his life philosophy is, he laughingly replied: “Just keep walking, everything is changing, so we must keep moving forward. It’s important to carry on for the next generation and to keep the soul of these beautiful communities alive and thriving.”

Share your thoughts