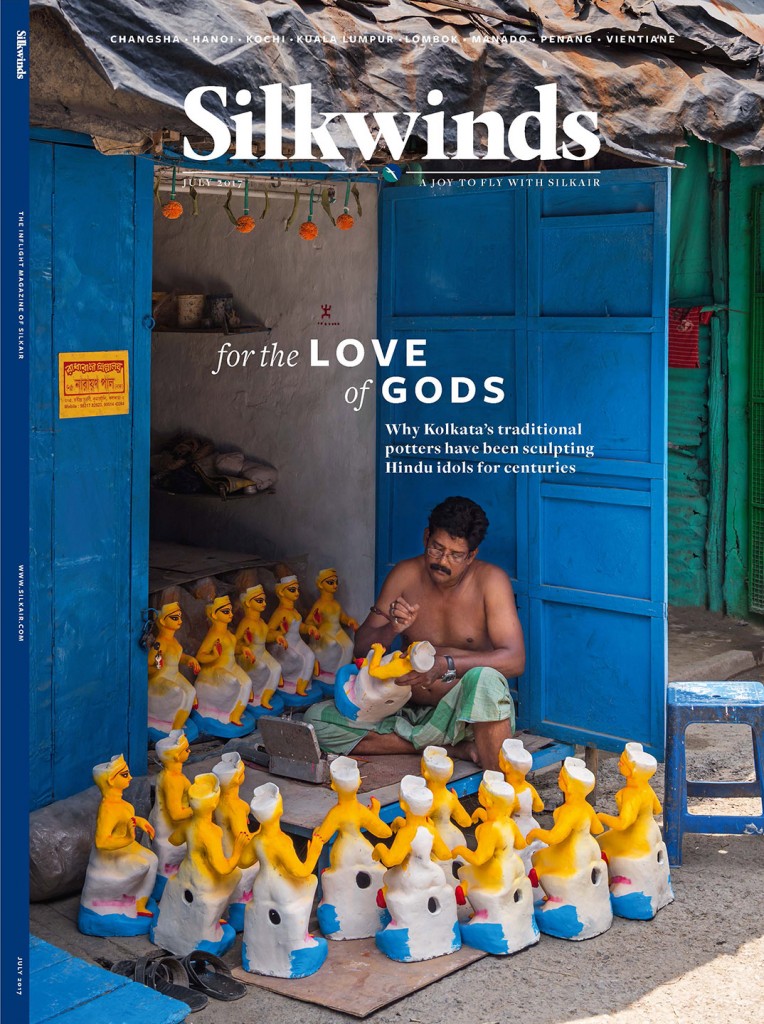

In a rickety hut by the Hooghly River, a row of female deities

stands oblivious to the searing heat. Missing their hands and feet,

and coloured only by a beige coating of clay, these life-size models seem

quite ordinary at first glance. Yet, they’re on their way to becoming magnificent

Hindu idols, the ornate centrepieces of Kolkata’s many colourful religious ceremonies.

Most of these statues are created in the same small pottery village in Kolkata, a practice that has been taking place since the town became the capital of British India in 1772. Kolkata once had many such villages, each dedicated to a particular trade. Today, however, the potters’ quarter of Kumortuli is the only one of note that remains; the others have long been demolished as the city swelled in size. This ramshackle neighbourhood, which is home to more than 200 potters, vibrates with artistic endeavour.

– Ronan O’Connell, Silkwinds

For four sweltering days this past May, I meandered the dusty, narrow lanes of Kolkata’s Kumortuli, visiting with and documenting the kumors (Bengali for potters) who craft the colourful Hindu goddesses that grace pujas (religious ceremonies) across the state of West Bengal. Kolkata is home to three major puja festivals, each assigned to a different Hindu goddess: Saraswati Puja, dedicated to the goddess of learning and arts (Jan/Feb); Kali Puja, committed to the destroyer of evil and the figure of divine motherhood (Oct); and Durga Puja, devoted to the warrior goddess (Sep/Oct).

As writer Ronan O’Connell details in this month’s Silkwinds magazine cover story, “for many generations, this reliance on the three biggest rituals created hardships for Kumortuli’s artisans…[which] resulted in many potters turning their backs on this traditional career. In the past few years, however, fortunes have turned. Today, due to societal changes, the devotional focus in Kolkata has now widened to include deities such as Rama and Ganesha. Puja festivals that had once been relatively minor in Kolkata, such as Ram Navami and Ganesh Chaturthi, are growing in scale…

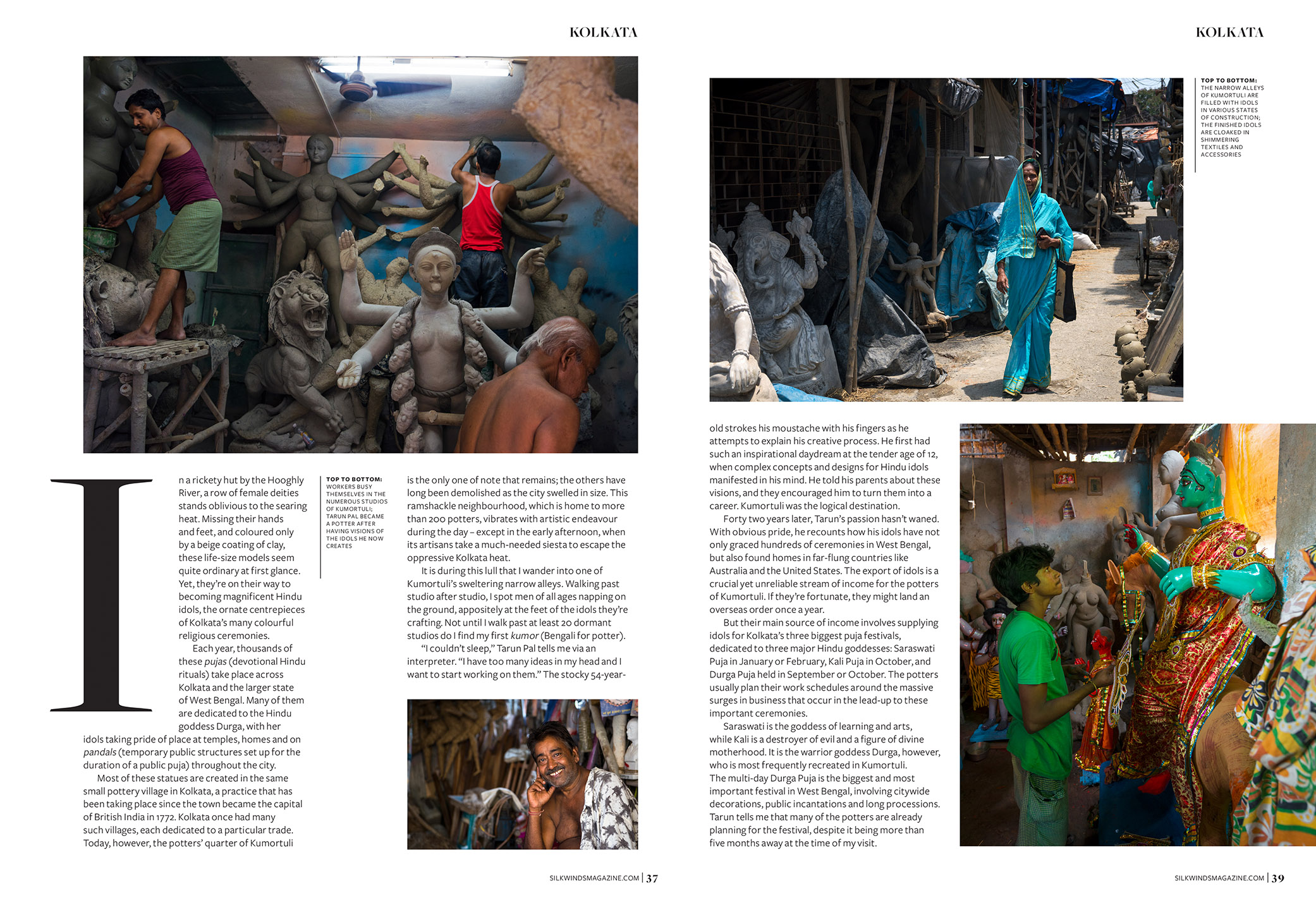

“The idols, which range in height from two to three metres, can fetch between INR16,000 (USD$250) and INR30,000 (USD$465). These price tags are well-warranted, as considerable work goes into the construction of an idol. Each deity is usually crafted by a team of between three and five artisans… who prepare the [bamboo] structure of each statue… before wrapping it with [and applying] a malleable clay on the contours of the frame [including

creating] its feet, hands and head with clay… [Then] when the whole frame has been layered, [it is wiped] with a cloth soaked with wet clay to prevent any cracks from occurring once the statue dries out.

“Once dried, the painting can begin, a prestigious task that is typically reserved for senior artisans. After an initial coat of white paint, the idol is decorated with an array of vibrant colours. The entire process reaches its artistic apex when it comes to the idol’s eyes. So revered is the act of painting the eyes of a deity that the artisan will often ritually cleanse himself with water — and sometimes meditate — before doing so. The final step sees rope-like hair glued onto the idol, which is then clothed with various shimmering textiles.”

It is a physically taxing, labour-intensive process — one that hasn’t changed in more than half-a-century — and it was fascinating to experience and document. As 80-year-old artisan Nitai Pal, who has been working in Kumortuli since he was 20 years old, explains, “The materials are better now, the workmanship more accurate. But the skills are the same. Tradition is important, and we have kept that going here.”

Following is the cover and feature that I photographed and Rowan authored for the July 2017 issue of SilkAir’s Silkwinds inflight magazine.

Browse a larger collection of the photography I made while on assignment in Kolkata.

1 Comment

Join the discussion.

Great Pix