Here, fire breathes life, and water and floods mean almost

certain death. Where in the evenings, the moon sets rather than rises in the sky,

leaving the stars to shine unencumbered. And while the land is seemingly barren,

it becomes clear that it is rich in both history and spirituality.

In the middle of 2018, writer Stephanie Zubiri and I were commissioned by Silverkris, Singapore Airlines’ inflight magazine, to travel 3,000km on an grand train journey from Darwin to Adelaide aboard The Ghan, the longest North to South rail crossing in the world. This month, our friends at Travel + Leisure Southeast Asia published online a broader selection of my photography — along with Stephanie’s first-person account — of the adventure.

“Australia is mostly empty and a long way away,” Bill Bryson writes in his book In A Sunburned Country, continuing that it “is the driest, flattest, hottest, most desiccated, infertile, and climatically aggressive of all the inhabited continents…This is a place so inert that even the soil is, technically speaking, a fossil.” Let’s not forget that it is also home to an inordinate amount of deadly animals, including the world’s most poisonous snake, an array of toxic spiders and a handful of apex predators with very large jaws and serious teeth.

Why on earth, then, would I spend four days snaking along on the ground, on a train, traversing the desolate and potentially dangerous Red Center? My intention was to slow down, relax and contemplate my life, to allow myself to be hypnotized by the rhythmic clickety clack of the tracks. However, what transpired couldn’t have been further from my expectations. As soon as I stepped foot on The Ghan, I was thrown into an exciting adventure, an in-depth exploration of the heart of Australia, and a discovery that took place not just in the outback, but within the confines of the carriages.

Chugging close to 3,000 kilometers across the continent from Darwin to Adelaide, The Ghan is an epic train odyssey that is steeped in history and holds the record for the longest North to South rail journey in the world. Originally named the Afghan Express, The Ghan pays homage to the pioneering Afghan cameleers who blazed a trail into Australia’s Red Center from the 1860s to the early 1930s. For the past 90 years, the route has been vital in providing access to the isolated outback.

Do not bring a book. You will leave it untouched and unopened. I learned this as soon I got myself settled in the lounge car. I had barely sat myself down when I was asked where I was from and what I was doing there. My coffee was quickly traded for Sauvignon Blanc and the introductions went on and on. There was no such thing as quiet time on this train. I suppose if you decided to hole up in your berth and be anti-social you could, but isn’t the point of slow travel to meet other voyagers?

Although the passenger demographic was noticeably older, the pace was decidedly not relaxed. One night while I was having dinner with Claire, a beautiful retiree from Auckland, I made a passing comment about how there was, perhaps, too much to do on the schedule. She looked at me with a twinkle in her eye and exclaimed: “I can read a book any day! I think every minute is wonderfully organized and I wouldn’t miss a second of adventure.”

Adventure was definitely on the menu. Our first excursion was at Nitmiluk Gorge where I was instructed to hang on to my hat, because if it blew into the croc-infested water, there was no jumping after it. Our guide, Jamie Brookes, nonchalantly expressed that if I did, I would not be saved: “The first time you see a croc is when their jaws are about to crunch on you. There is no screaming that happens, just a swell of water, then you’re gone.” Yeesh.

Simpson’s Gap, just outside Alice Springs was no different. During a hike through the outback, we were told to stomp our feet to scare off any snakes, and to steer clear of the ghost gums. Often called “widow makers,” gum trees kill off and spontaneously drop their unnecessary branches in order to survive, inadvertently exterminating unsuspecting victims resting underneath. It was difficult terrain — you had to accept that death was looking at you right in the face in order to survive. You couldn’t go about in blissful ignorance; you had to listen to the cues and tune in to your environment. “That’s what the indigenous Australians do,” shared another guide, Jo Lyons. “They stop and listen to the wind. They listen to the land. We don’t own the land. The land owns us.”

As we reached the top of Cassia Hill, I took a moment to breathe, to close my eyes and listen. The bracing wind swept over me. Sounding more like crashing waves than howling gusts, it was full of energy, of life and death, of struggle and sorrow, of promise and hope. Of a forgotten past and ancient wisdom. I listened and it gave me an answer, a little whisper that crept into my heart. I heard a nature that yearned to speak. Suddenly, the gums no longer looked ghostly, they resembled wizened spirits from a time past, ready to share their knowledge for anyone who wished to honor it.

The existential moments I searched for were not discovered in stillness and quiet, but rather emerged from a deep immersion into a world that was seemingly topsy turvy. Where fire breathes life, and water and floods meant almost certain death. Where in the evenings, the moon set rather than rose in the sky, leaving the stars to shine unencumbered. And while the land was seemingly barren, it became clear that it was rich in both history and spirituality.

It was also found in the laughter and carefree energy that permeated the experience. From the cheeky sense of humor the locals possessed to that one night after a barbecue at the historic Telegraph Station in Alice Springs, where we all tipsily danced under the starlight to the happy strains of “Stuck in the Middle with You.”

It’s so hard to keep this smile from my face,

Losing control, yeah, I’m all over the place,

Clowns to the left of me, jokers to the right,

Here I am, stuck in the middle with you

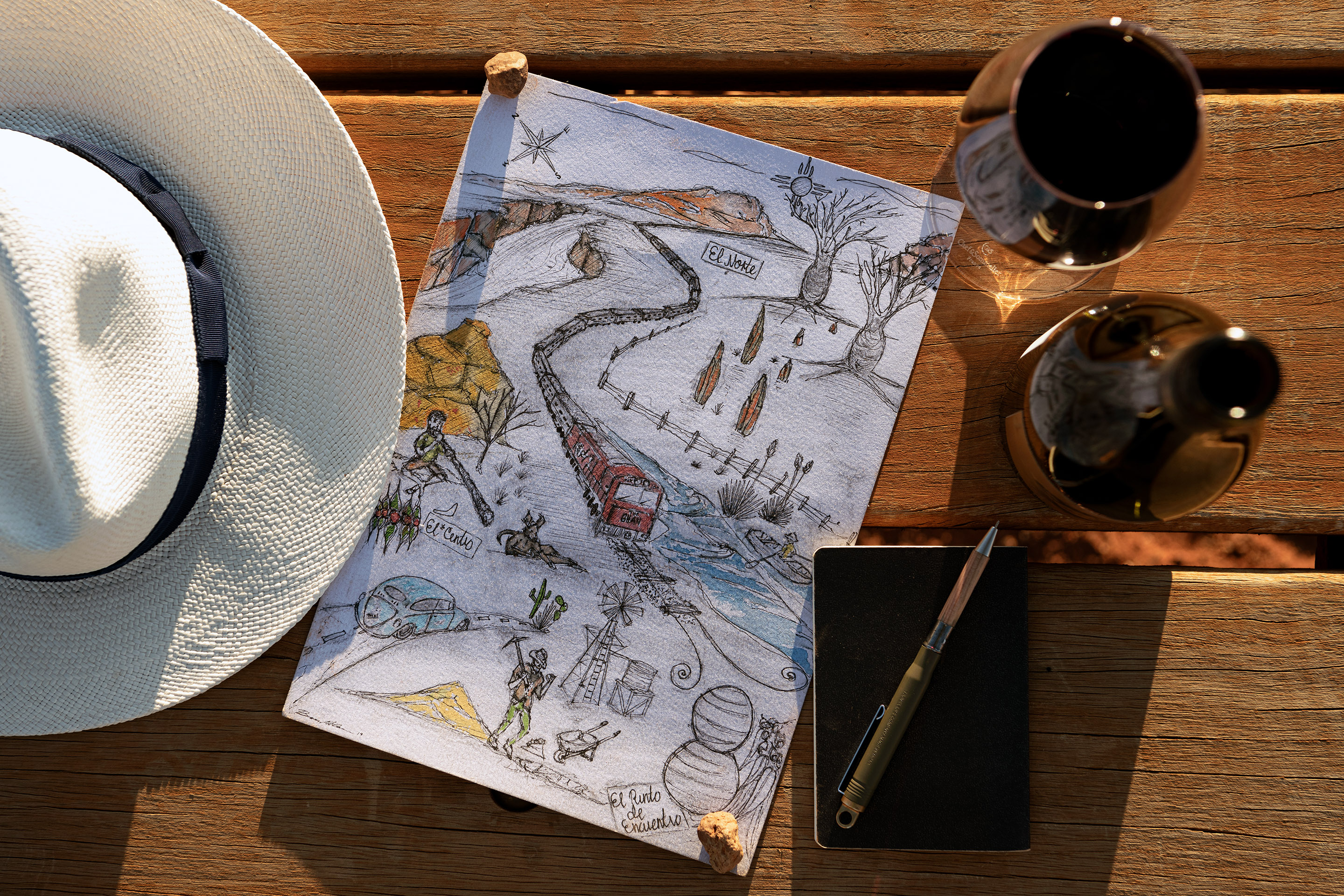

As the trip came to a close, I contemplated the map of the journey that Ben McCallum, the train’s barista drew and painted for me. Not quite a map, but more of a deeply personal representation of the entire expedition. Perhaps not all maps are meant to be accurate, and this voyage was less about the locations and more about how they made you feel. It was about chance meetings and nuggets of wisdom from the characters encountered both on and off the train. About the spiritual energy that emanated from that barren, but inherently rich red earth, proving that when you embrace Australia for its ruggedness, and face the dangers and fears head on, with respect and reverence, it will inhabit your soul.

In what was several times a movie set for dystopian sci-fi films lives a population of 1,900 people representing 46 different nationalities. The opal mining town of Coober Pedy was founded in 1915 and continues to supply most of the world’s gem-quality opals. Rusty junkyards, dusty roads and “dugouts” — homes literally carved out of the ground — all give Coober Pedy a ghost town vibe. Due to high temperatures and harsh desert climates, almost all the action happens underground. While overall there isn’t much excitement going on in the town, things can still get pretty explosive as residents tend to turn to dynamite measures to settle disagreements. The proof is the fairly new police station, which had to be rebuilt in 1990 when a miner blew up the precinct after being pulled over for drunk driving and was unhappy with his fines.

The brush landscape felt barren, burnt and scorched, with grey and black scabs on a parched red earth. “The land looks desolate and dry,” said guide Jo Lyons, “but it’s far from it. Underneath the arid soil flows fresh water and there are so many things here that are full of life. The indigenous population sees this land as their supermarket, hardware store and chemist,” she explained pointing to the Tea Trees and various shrubbery. “They would set up camp somewhere and live off the land. When they were done, they would set everything on fire. They would naturally practice patch burning. From the ashes, new greenery would grow and life would come back. Even certain seeds need the flames to pop open and grow.” It seemed as though life and death depended on each other; that mortality was everywhere and without it there would be no birth.

The sandstone escarpments towered majestically all around us. Set against the clear bright azure sky and dotted with greenery, the jagged rock surface looked like carved faces. Every corner we turned, it seemed as though there was an audience perched on high, looking down onto the gorge. It came as no surprise when guide, Jamie Brookes, articulated that it was very ancient land. One-point-six-five-oh billion years ancient, to be exact. The rocks held no fossils as they were even older than prehistory. “The Jawoyn and Dagomen people believed that the spirits of the land told the people how to survive,” he explained, himself part of the Dagomen, who married into the Jawoyn. “You had to continuously appease the spirits of the land and if you didn’t take care of it, you died.” As we went on our cruise and exploration, in what seemed like a natural reverence to the sublime nature and history, the boat took on hushed tones. The sacred was palpable.

For one anomalous passenger, K.J., a 10-year-old from Singapore, adventure was the entire purpose of this trip. “I was reading a book by Bill Bryson called In a Sunburned Country and I really wanted to experience the outback that he did.” The young boy spoke extensively about his love for train travel, his yearly trips with his father, Mark, and his thoughts on his favourite authors. It was clear to me that meeting someone as unique as K.J., bright and inquisitive, was one of the reasons one would go on a journey like The Ghan. To be able to glimpse, if even for a moment, the world through his eyes is such a gift.

Unlike other luxury train that are more stuffy and formal, The Ghan has a vibrant energy. The staff is incredibly young and dynamic, operating with ease and amiability. Each staff member takes on different roles throughout the journey and you have plenty of opportunities to listen to their stories. The train manager, Sam Whaley, is just 33 but has been working on The Ghan for 13 years. Without any previous hospitality experience, he applied on a whim and has loved every minute of it. “There’s different scenery every day, every sunrise and sunset is going to be different, so is every night sky and the stars,” he explains with a dreamy look. “I’ve been lucky for so many years. I’ve been able to float from role to role, crew to crew, and been on different journeys, but it’s really the guests. It’s their expressions and experiences, when you see them see it for the first time.” It’s exactly this fluid and friendly energy that is the signature of The Ghan. The experience is not so much orchestrated for the guests but shared with them.

As I was getting my latte one morning, I discovered that Ben McCallum, the barista, liked to sketch. “It’s just a hobby that I do for fun,” he explained about the little bits of receipt paper covered in ink and imagery. We had been looking for a pretty map to photograph and Ben immediately volunteered to draw us one. “I can’t promise much, but perhaps I can pick up some watercolor at Alice Springs.” This was another example of the warm and personal service they offered: from how they chose to place people together in the dining cars to remembering that you preferred almond milk in your flat white. Everything is thoughtful and intentional without being overly contrived or intrusive.

With 36 carriages spanning a ridiculous one kilometer, the train is shockingly long. Built for comfort and luxury, it is the perfect way to travel indulgently cross country without any hassles.

One evening, the staff prepared an outdoor barbecue by the historic Telegraph Station of Alice Springs. People went on camel rides while the band played classic-rock tunes accompanied at one point by a homemade PVC didgeridoo. It all felt caravan-esque. By then, everyone was on a first-name basis, welcoming each other with warm smiles and their insightful stories from the day. The sense of community and camaraderie was building among the passengers and staff alike — all of us travellers seeking, and finding, connection.

Share your thoughts